Talks, field trips and events organised by west country geological organisations are publicised on this blog. Discussion about geological topics is encouraged. Anything of general geological interest is included.

Saturday 19 December 2020

Origins of Life

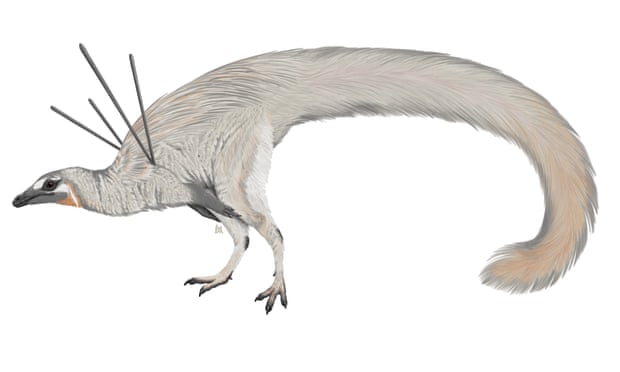

Strange Dinosaur

Strange Dinosaur

Wednesday 16 December 2020

Neanderthals etc.

Neanderthals etc.

Saturday 12 December 2020

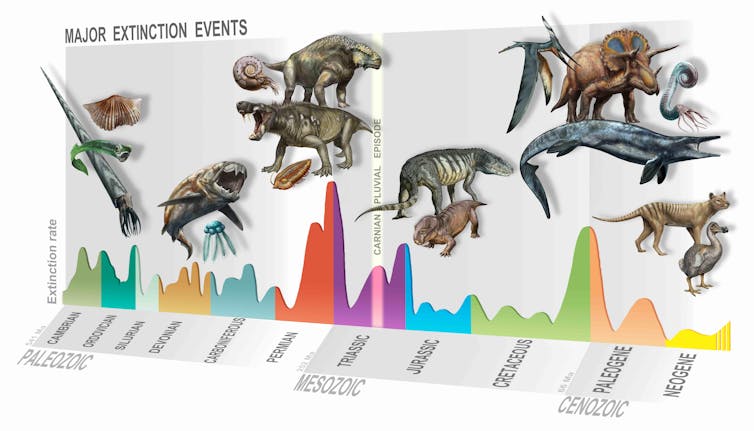

Are Mass Extinctions Cyclical?

Are Mass Extinctions Cyclical?

Sunday 6 December 2020

Shropshire Geol Soc Zoom Lecture

Shropshire Geol Soc Zoom Lecture

Wednesday 2 December 2020

Doggerland and Storegga Tsunamis

Doggerland and Storegga Tsunamis

Monday 30 November 2020

Footnotes November 2020

Footnotes November 2020

Monday 23 November 2020

DOWN TO EARTH EXTRA - December 2020

DOWN TO EARTH EXTRA - December 2020

Saturday 21 November 2020

Back Numbers of Magazines Available

Back Numbers of Magazines Available

Tuesday 17 November 2020

Urban Geology (mostly London, I'm afraid)

Urban Geology (mostly London, I'm afraid)

Two sections through once articulated valves of L. gibbosa, now

leached away. By chance, the mason has cut through along the long axes of the shells

giving the effect of ‘angel wings’. The ribs and costae can be seen on the upper

example of the two. Once again, this is from the Roach used on the new wing of BBC

Broadcasting House.

One photograph illustrates that this is indeed Urban Geology - the scale is indicated by a fag end!

I have just started reading this huge archive and it is a cornucopia of geological insights and delights! A pity it is mostly in London.

Saturday 7 November 2020

Food Webs - Back to Basics

Food Webs - Back to Basics

Friday 6 November 2020

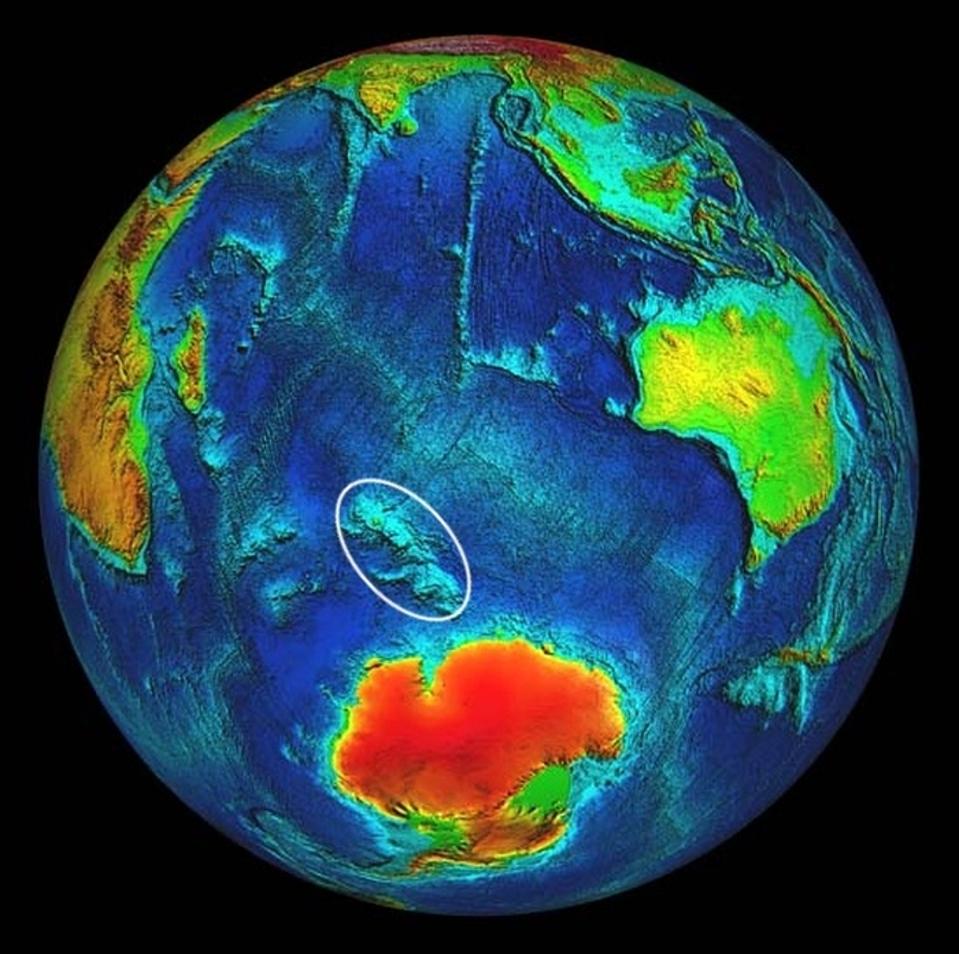

The Longest Erupting Supervolcano ---?

The Longest Erupting Supervolcano ?

--- Kerguelen!

Wednesday 4 November 2020

Geological Ladies

Geological Ladies

Friday 30 October 2020

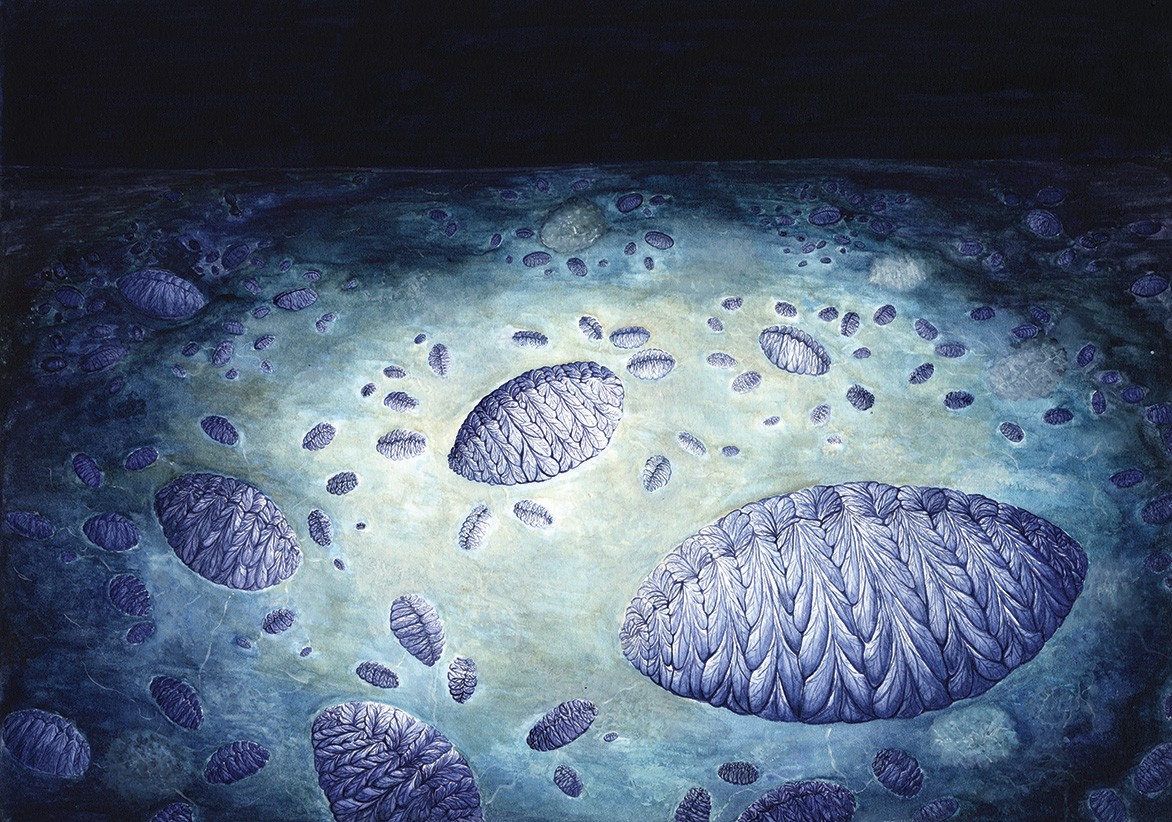

Get Up To Date with the Ediacaran

Get "Up To Date" with the Ediacaran

Thursday 29 October 2020

Evolving Pterosaurs Become More Efficient

Evolving Pterosaurs Become More Efficient

Pterosaurs increased their flight efficiency over time – new evidence for long-term evolution

With a wingspan of 12m–15m, Quetzalcoatlus was one of the largest flying animals that ever lived. Indeed, it seems astonishing that such monsters could fly at all. Yet over a period of more than 150 million years, pterosaurs (the flying cousins of dinosaurs) became increasingly efficient at flying as they evolved from small animals the size of a starling to become giants of the sky.

Our new research shows that pterosaur flight efficiency improved by 50% over the period from 230 million years ago to their extinction 66 million years ago. This enabled them to fly for over much greater distances for long periods of time.

This may seem like a remarkable or even foolhardy conclusion to draw from a study of fossils, but we have developed methods to extract the data. What’s more, this finding goes to the roots of how Darwinian evolution works, suggesting that lifeforms can continue to adapt to their environment over very long spans of time.

Pterosaurs were active, warm-blooded animals, insulated with whiskery feather-like structures all over their bodies. They flew using leathery wings made from skin supported by an especially long fourth finger that extended from their elongated arms.

To calculate the efficiency with which different pterosaurs flew, we first needed to know how heavy they were. So we made estimates based on the size of 16 species for which we have relatively complete skeletons and cross-checked our figures with those of birds and bats to make sure they were reasonable.

We also estimated the basal metabolic rate (BMR, the energy expended by an animal when at rest) for each pterosaur species from a large sample of BMR and body mass measurements for birds. We were then able to create an “efficiency of flight index” based on estimates of how much energy each species would have needed to travel at its ideal speed, just fast enough to defy gravity, relative to its body mass.

By modelling reasonable values for other species, we came up with figures for 128 different pterosaurs, which we then mapped on an evolutionary tree that showed how flight efficiency changed over time as the species evolved. We found that for all pterosaurs except azdarchoids, there was a significant increase in body size, wingspan and flight efficiency. We used what’s known as a “Bayesian modelling approach” that repeated and improved the analysis billions of times, considering all possible combinations of all possible sources of error.

Body mass rose from a mean of 0.6kg in the Middle Jurassic epoch to 6.05kg in the Late Cretaceous. In the same time, mean flight efficiency increased substantially. Much of this increase in efficiency was related to increasing body size – bigger pterosaurs naturally flew more efficiently. But once body size was excluded, we found that flight efficiency still increased by some 50%.

The azhdarchoids, a group of pterosaurs with very long legs and necks, seem to have bucked the trend and showed decreasing flight efficiency with increasing body size. They were evidently following their own evolutionary route to excessively huge body sizes, meaning that evolving to become larger gave them other advantages on the ground and they became less dependent on flight to get around.

A test of Darwinian evolution

Our findings don’t just tell us something interesting about pterosaur evolution, but provide useful evidence about evolution itself. A core assumption of Darwinian evolution is that adaptation by natural selection drives successful organisms to improve in some way. Within populations, the fittest organisms survive, and their fitness is measured not only in their successful adaptations but also because they breed and pass on their successful genes.

An important question for scientists has long been whether we can measure these improvements through longer spans of time, say between species and over millions of years. In arms races between predators and prey, the lion runs faster to catch its prey, but the wildebeest runs faster to escape. But they don’t keep evolving faster and faster speeds forever – ultimately they are limited by material constraints.

In 1973, evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen put forward his “Red Queen hypothesis” of Darwinian evolution to try to resolve this conundrum. Van Valen realised that the environment in which an organism lives is not constant but is changing all the time. And so the organism has to keep evolving and adapting just to maintain its status quo. As the Red Queen in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass said: “It takes all the running you can do to stay in the same place.”

Our results suggest that organisms can become more efficient over a very long period of time. The Red Queen hypothesis likely explains most situations where organisms are in some kind of balance with each other within their ecosystems. But our work shows that actual net improvements in physical performance can happen. This perhaps supports a central assumption of Darwinian evolution that has been nearly impossible to test until now.![]()

Michael J. Benton, Professor of Vertebrate Palaeontology, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday 26 October 2020

How to Survive a Landslide

How to Survive a Landslide

Before

Check if there are potential dangers of a landslide.

Live in the downhill side of a house.

During

Move upstairs

Go to interior, unfurnished areas

Open downhill doors and windows

After

Make noise so rescuers can find you

Don't

Open a door out of curiosity

Shelter beside large furniture

The article goes into much more detail, giving reasons for the survival strategies.

P.S. In the accident near Stonehaven it wasn't the landslide that caused the deaths but the train being derailed when it ran into the relatively small amount of landslide debris.

Down to Earth Extra - November 2020

DOWN TO EARTH EXTRA - November 2020

Thursday 22 October 2020

Rain Erodes Mountains - Measured and Modelled

Rain Erodes Mountains - Measured and Modelled

Tuesday 20 October 2020

Gilbert Green RIP

Gilbert Green RIP

Monday 19 October 2020

Naughty Fossils?

Naughty Fossils?

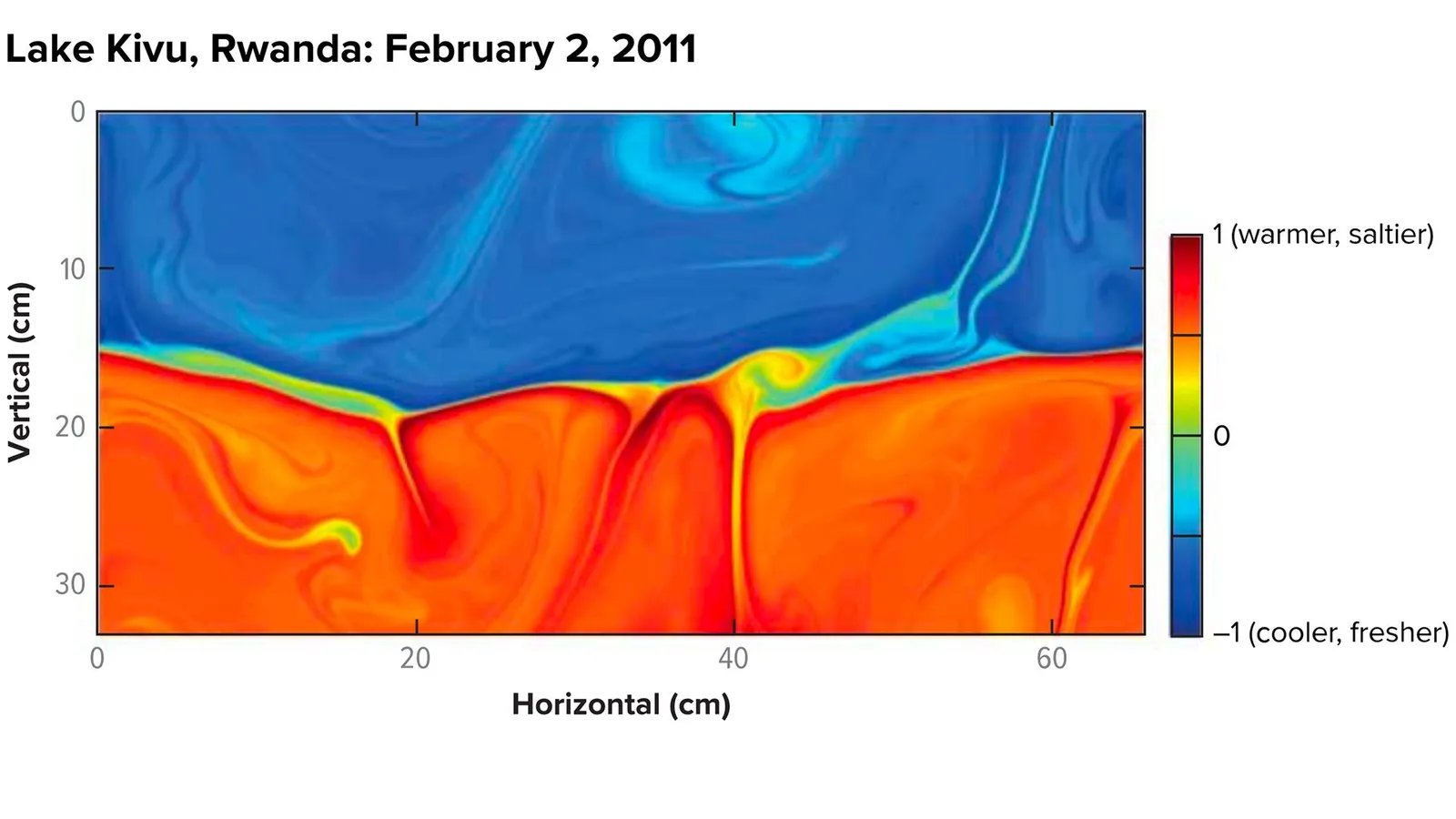

Lake Kivu - Dangerous and Useful!

Lake Kivu - Dangerous and Useful!

The unusual separation of layers of the lake is at the core of its volatility (Credit: D Bouffard & A Wuest/AR Fluid Mechanics 2019/Knowable Magazine)

Thursday 15 October 2020

Mammals are Warm Blooded - not Quite!

Mammals are Warm Blooded - not Quite!

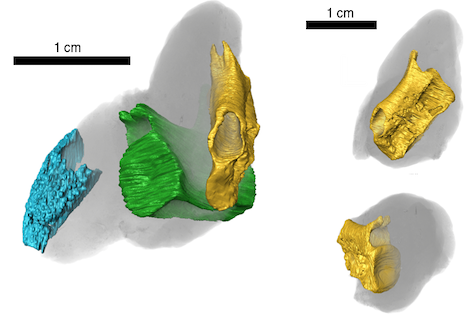

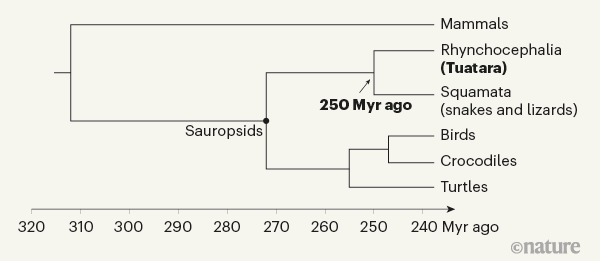

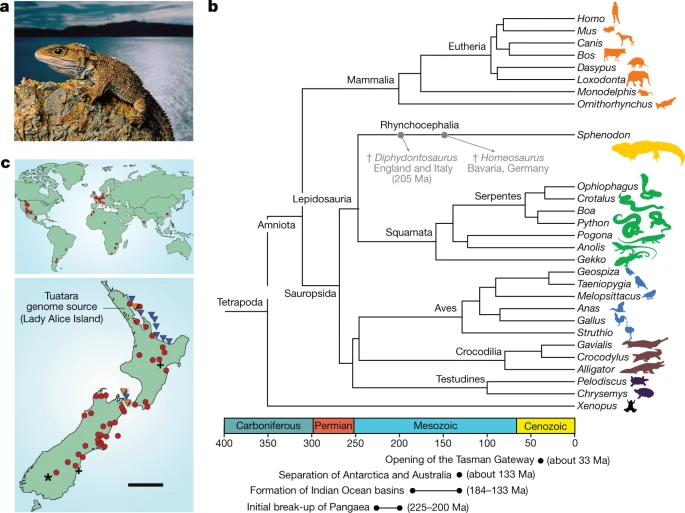

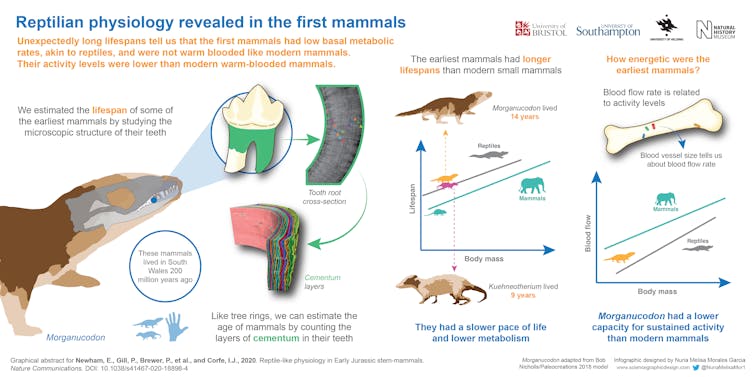

Fossilised teeth reveal first mammals were far from warm blooded

Warm blood is one of the key traits that led to the success of mammals as they evolved from scurrying beneath the feet of dinosaurs to spreading into the wild and wonderful collection of animals we know today. But our new research, which involved X-ray scanning hundreds of fossilised teeth, suggests the first mammals were more like cold blooded reptiles, and that warm blood evolved much later.

Warm blood helps us maintain our body temperature regardless of our environment, allowing us to gather food at night and in cold climates, and helps us stay active for longer than our cold blooded relatives. However, exactly when, why, and how this evolved is still poorly understood.

We know from tiny fossils of bones and teeth that mammals first evolved over 200 million years ago, and had many of the traits we associate with mammals, such as specialised chewing teeth and bigger brains. But the physiologies (how an animal’s body works day-to-day) of these animals is difficult to estimate using traditional methods, as this relates to soft organs that aren’t usually fossilised.

Our new research, published in Nature Communications, now offers a glimpse into the physiologies of the first mammals, by pioneering X-ray imaging to count growth rings in their teeth and measure blood flow through their bones. Although it had previously been assumed that even the earliest mammals were warm blooded, this research suggests that they still had some way to go before developing warm blood and its benefits that we enjoy today.

Long lifespans and slow metabolism

Working with a 20-strong international team of scientists, we have estimated the lifespans of the earliest mammals for the first time. This was done by X-ray scanning hundreds of fossilised teeth found in south Wales of two tiny mammals, Morganucodon and Kuehneotherium, from the Early Jurassic epoch.

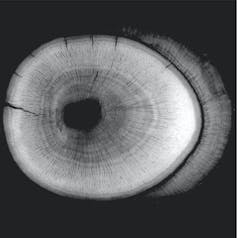

High-resolution scans performed at powerful “synchrotron” X-ray sources in Switzerland and France allowed us to count annual growth lines preserved in the fossilised cementum of these teeth. Cementum is the little-known tissue that anchors mammal tooth roots to the jaw, recording every year of an animal’s life by growth lines that can be counted like tree rings to estimate lifespan.

These lines are counted in living mammals by grinding teeth down into thin sections that can be studied using microscopes. As this destroys the tooth, we could not do this with precious museum fossils, and so we used X-ray imaging. Counting rings in our fossil mammal teeth gave a lifespan of 14 years for Morganucodon, and nine years for Kuehneotherium.

These are significantly, and surprisingly, longer lifespans than those of similar, shrew-sized mammals living today whose wild lifespans rarely exceed two to three years. This suggests a dramatically slower metabolism, or pace of life, than living mammals, and instead more closely resembles that of living reptiles.

Low activity levels

The size of the openings for the major blood vessels running through an animal’s limb bones is known to be proportionate to the levels of sustained activity (such as hunting and foraging) that they are capable of: smaller size suggests lower activity levels.

When we measured this in the femur of Morganucodon, we found that, while smaller than living mammals, they were also higher than those of living reptiles. This suggests that early mammals had an intermediate ability for sustained activity, between warm blooded mammals and cold blooded reptiles.

This combined approach of studying the lifespans and activity levels of early mammals provides the first direct window onto several aspects of how they lived. We can see that our earliest relatives kept a much slower pace of life, but had definitely started on the road to the active lifestyles of living mammals today.

We shall continue these studies through the early mammal fossil record, to shed light on the first steps towards the modern mammalian lifestyle, and when we truly became warm blooded.![]()

Elis Newham, Research Associate in Palaeontology, University of Bristol and Pam Gill, Senior Research Associate in Palaeontology, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thursday 8 October 2020

Build the Alps - Pulling or Pushing?

Build the Alps - Pulling or Pushing?

Friday 2 October 2020

Neanderthals at Risk from COVID-19?

Neanderthals at Risk from COVID-19?

Wednesday 30 September 2020

Down to Earth Extra - October 2020

DOWN TO EARTH EXTRA - October 2020

Tuesday 29 September 2020

Viruses can be Fossilised

Viruses can be Fossilised

Monday 21 September 2020

Another Mass Extinction!

Another Mass Extinction!

Saturday 12 September 2020

Where Does the Carbon in Diamonds Come From?

Where Does the Carbon in Diamonds Come From?

|

| Diamond crystal containing a garnet and other inclusions (Credit: Stephen Richardson, University of Cape Town, South Africa) |

Friday 4 September 2020

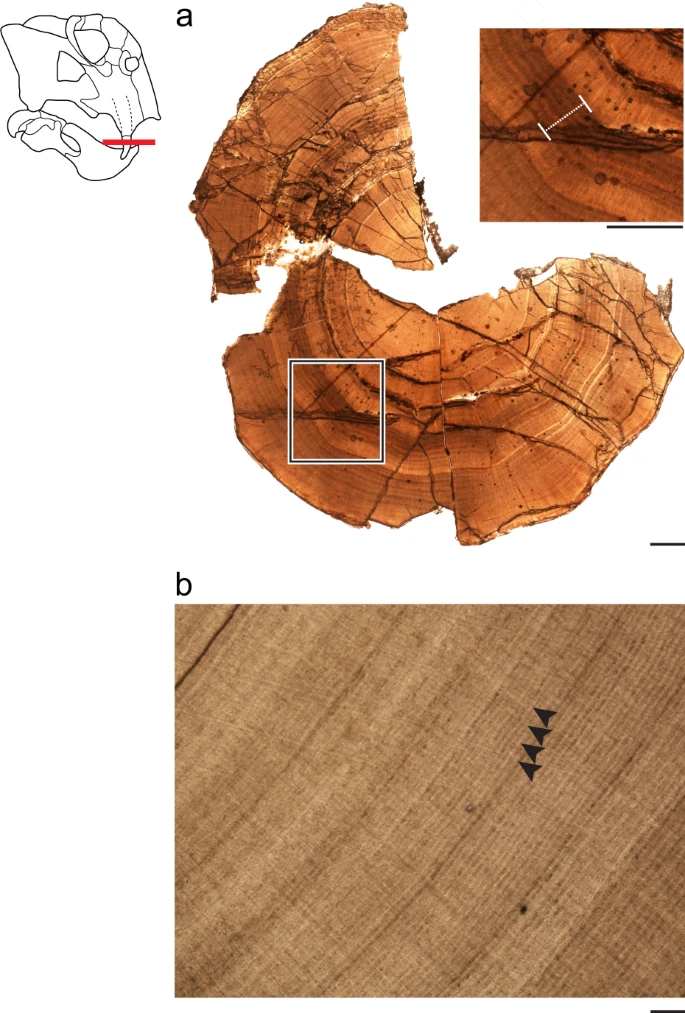

Hibernation is Not New

Hibernation is Not New

|

| a A cross-section of Antarctic specimen UWBM 118025 with a “hibernation zone” highlighted at a higher magnification. Scale bars = 1000 μm. b Well-preserved regular incremental growth marks from the South African specimen UWBM 118028, lacking “hibernation zones”. Arrows denote individual lines with an average spacing of 16–20 μm. Scale bar = 100 μm. The authors argue that this indicates the Antarctic creatures were hibernating - or something very like it. Which is not really surprising but nice to have some evidence for it. The original article is HERE. |